Their Day in Court

Across the developing world, the Sudreau Global Justice Institute at the Caruso School of Law is creating solutions for some of the most pressing problems in the criminal justice system

In 2018, Mary,* a gentle grandmother from Malawi with no prior criminal history, was traveling in Ghana for a church conference. While in Ghana, Mary’s boss asked her if she could pick up medicine for him that was not available in Malawi. Although the medicine was not an illegal drug, Mary was stopped in the airport by customs officials and arrested for unknowingly breaking a new law in Ghana’s Public Health Act meant to target and fine large companies selling the types of unregistered medicines Mary was carrying.

The judge issued Mary the minimum sentence of 15 years in prison or a $15,300 fine. Unable to pay the fine, Mary, an unfortunate victim of a loophole in the new law that was never intended to target people like her, was incarcerated and has been in a Ghanaian prison separated from her family for more than two years. Although Mary’s case has not yet been resolved, a team of attorneys in Ghana has been working fervently to fight for justice on her behalf so she may be released from prison and reunited with her family.

“In many places around the world, if someone is arrested and incarcerated they will likely wait several years in pretrial detention before having an opportunity to speak to an attorney for the first time,” says Cameron McCollum (JD ’17), director of the Sudreau Global Justice Institute (SGJI) at the Caruso School of Law. “Imagine being falsely accused of a crime and arrested but being unable to access an attorney to help you because you can’t afford one, and the government can’t provide one. On top of that, because of the systemic case backlog within your country’s justice system, your opportunity to prove your innocence at trial won’t come for years—you’re stuck. That is the reality for countless people around the world whose countries don’t offer a robust public defense system and that is why we engage in defense advocacy. We think that in the countries we work, we can change the average wait time to speak to an attorney from a few years to a few days.”

Since 2007 SGJI has provided invaluable and transformative resources to governments and legislators around the world through its initiatives in international human rights and religious freedom, advancement of the rule of law, and global development. The institute, formerly known as the Global Justice Program and endowed by alumna Laure Sudreau (JD ’97) in 2017, partners with organizations such as the International Justice Mission (IJM) to create a lasting impact in the lives of the Pepperdine law community and those experiencing injustices in the world’s most vulnerable places.

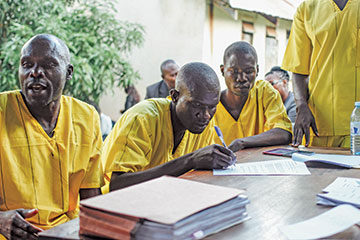

Currently SGJI is working with the Ugandan government to establish the nation’s first-ever public defender’s office. SGJI is nearing the end of the pilot phase of this project and plans to begin expanding across the entire country in the next few years. The team, which is composed of mostly Ugandan lawyers, recently visited four prisons in Uganda, engaging 105 clients and resolving 23 cases in one week. Many of the represented defendants have already been released or will be released and reunited with their families in a matter of days.

“We view ourselves as a catalyst to get the wheels of justice turning, but at the end of the day, this is all about serving and empowering our Ugandan partners to lead their own justice transformation,” says McCollum.

“Our goal is for the public defender’s office to be entirely Ugandan led and funded within five years.”

SGJI’s success in Uganda has led to several new opportunities for the institute to expand its reach and impact. In fall 2019 the institute signed an agreement with IJM to collaborate on several different initiatives around the world. These initiatives include faculty research collaboration, opportunities for students to engage in anti-human trafficking work, and a partnership to develop a framework for improving national prosecutorial systems through plea bargaining—an agreement negotiated between the prosecution and defense that grants the individual accused of a crime an agreed-upon period of incarceration or a range of potential imprisonment to remove the uncertainty of a trial.

An Innovative Expansion

A year prior, president Jim Gash (JD ’93), then a professor of law at Pepperdine Law,

was in Washington, DC, signing a memorandum of understanding between IJM and the Ugandan

Justice, Law, and Order Sector. While there, the field office director for IJM in

Gulu, Uganda, Will Lathrop, suggested that Pepperdine expand into West Africa and

consider providing Ghana the type of transformative assistance the law school had

provided to Uganda’s criminal justice system since 2009. Both countries, as well as

many others in the region, are significantly challenged by the same difficulties in

providing timely access to representation for those facing criminal charges.

A year prior, president Jim Gash (JD ’93), then a professor of law at Pepperdine Law,

was in Washington, DC, signing a memorandum of understanding between IJM and the Ugandan

Justice, Law, and Order Sector. While there, the field office director for IJM in

Gulu, Uganda, Will Lathrop, suggested that Pepperdine expand into West Africa and

consider providing Ghana the type of transformative assistance the law school had

provided to Uganda’s criminal justice system since 2009. Both countries, as well as

many others in the region, are significantly challenged by the same difficulties in

providing timely access to representation for those facing criminal charges.

After a day of meetings with various members of Ghana’s highest legal counsel, an agreement was made that secured the promise of assistance from Pepperdine faculty, staff, students, and alumni, as well as interns and fellows on the ground year-round, to assist with the country’s delayed justice system and establish a plea bargaining system similar to that which Gash had spearheaded—with extraordinary results—in Uganda. In the coming year, the institute plans to expand into countries such as Guatemala, El Salvador, and Rwanda to partner on similar legal initiatives.

While plea bargaining is a powerful tool on its own, McCollum says it must be paired with strong public defense advocacy. In Ghana, SGJI has partnered with the local government as well as the United States Department of State to enact public defense and plea bargaining advocacy and legislation with plans to expand even further across Africa. The first steps of these partnerships include training sessions with the various governments who are interested in adopting these effective crime-reduction and -deterrence practices in their own legislative processes.

In December 2020 and March 2021, SGJI met virtually with more than 50 Nigerian judges, prosecutors, and defense advocates for a plea bargaining capacity-building exercise in collaboration with the Ogun State Ministry of Justice in Nigeria so they could develop the skills to take on the process themselves in the future.

“Many of the countries we work with have plea bargaining legislation on their books, but it’s never been used, so we partner with the government to provide training and expertise as they seek to get started,” McCollum says.

Using hypotheticals from mock files of common crimes, the workshops gave the Nigerian attorneys an overview and analysis of plea bargaining basics—both the theories and benefits of the process. The attorneys engaged in role-playing exercises and were coached on case-analysis strategies.

“We asked everyone to play both sides,” says McCollum. “The prosecutors were asked to play defense advocates and vice versa because it’s important to stress that plea bargaining requires a collaborative approach. What we commonly see, here in the US as well, is a mindset focused on ‘winning,’ which often means getting the maximum sentence (on the prosecution side) or the lowest possible sentence (on the defense side) rather than what’s just and fair for a client who is willing to plead guilty. Playing both sides and demonstrating a collaborative approach to plea bargaining is an important part of the training process.”

Serving Central America

An unexpected roadblock to introducing new legislation in regions with limited experience in alternative disposition mechanisms is public pushback on proceedings such as plea bargaining, which many perceive to be a method that reduces prison time for convicted criminals. In multiple countries in Central America, plea bargaining legislation was almost passed in 2018 but was ultimately shut down by local advocacy groups that were concerned the practice would lead to convicted criminals getting a get-out-of-jail-free card. To combat these inaccurate narratives, SGJI is involved in public awareness campaigns to educate, inform, and further understanding of the effectiveness of such legal practices.

McCollum explains that the concept of a reduced sentence is often misunderstood by the community and shares that plea bargaining not only initiates the conviction process, but it also introduces an appropriate conviction—for example, reducing a 50-year sentence to 46 years.

“The conviction rate for many crimes such as intimate partner violence is often really low because of evidentiary issues presented by the lengthy amount of time between arrest and trial,” says McCollum. “Many individuals —even those who have committed violent crimes—will not be convicted at all and will be released after sitting in prison for two years. The data shows that plea bargaining is a very effective practice to deter and reduce rates of crime while also decongesting case backlog and thus reducing arbitrary and unjust pretrial detention,” he says.

This spring law students Tara Aleagha and Rebecca Voth have been collaborating with several IJM offices in Latin America to provide research assistance on a policy brief. Their current project involves working with a group of female legislators in El Salvador who are advocating for change in the country’s intimate partner violence laws.

“El Salvador treats instances of intimate partner violence as a private, family matter,” says Voth. “Most of the time, if a victim reports abuse, the case goes to a family court where the victim and abuser participate in a mediation. There is no court process, and the abuser suffers no punishment. This policy brief supports those legislators that are advocating for the abolishment of this mediation process.”

Aleagha and Voth supplemented the IJM attorneys’ draft of the brief with legal argument contending that the prosecution of perpetrators of domestic violence is a more effective legal process than mediation.

Currently in the process of editing the brief, Aleagha and Voth have collaborated with an attorney and other members of the IJM staff in Guatemala to better understand the cultural context. While the brief was drafted in English, the students are writing it entirely in Spanish and have had a few meetings in Spanish with the country directors and attorneys in Central America.

Through her work, Voth hopes to correct the power imbalance inherent in intimate partner violence situations that mediation cannot properly address. She explains that mediation causes the victim more trauma and fails to provide a solution to the abuse. “Mediation assumes that parties are equal, and that is never the case when intimate partner violence happens,” she says.

“The failure to criminalize intimate partner violence sends the wrong message to society—that abuse isn’t really a crime.”

“We hope that this policy brief will give the El Salvador legislature a tool it needs to pass comprehensive reform on this issue,” Voth continues. “Ideally, El Salvador legislators will recognize the importance of imposing criminal sanctions on abusers and seek the safety of victims by implementing criminal penalties for intimate partner violence and eliminate mediation in this context.”

Aleagha, who anticipates that this experience will help her become a better civil servant, community member, and human being, hopes to impart her experiences at Caruso Law to a career that allows her to bring true justice to others. “This opportunity has opened my eyes to the countless ways we can help one another.”

Justice for All

The percentage of the prison population on remand—people who are sitting in prison not actually having been convicted of a crime—in the developing world remains massive. When Pepperdine started its work in Uganda, 70 percent of those in prison had not been convicted of a crime. That number recently fell below 50 percent nationwide. Partners across the University, such as Julia Norgaard, assistant professor of economics at Seaver College, have been assisting SGJI with gathering and analyzing data related to time on remand, case backlog numbers, and time on trial. In the near future, McCollum shares plans of SGJI’s expansion across the University in an effort to reinforce the idea that justice is not only a matter of law.

“We recognize that we live in a highly privileged and unique environment where we have access and the ability, if we do the hard work, to provide holistic justice solutions to communities,” McCollum says. “If you’re coming to Pepperdine as an undergraduate or graduate student, no matter what your passion or focus is, we want you to be able to use your skill set to serve people in need around the world.”

Beyond contributing legal expertise and training to regional governments and providing on-ground support from program directors, SGJI also creates jobs by hiring local attorneys in an effort to build thriving communities. More than that, SGJI’s primary measurable goal is to provide defense counsel and representation to anyone who can’t afford it. And while pretrial detention cannot be fully eliminated, McCollum hopes the efforts of SGJI can reduce or eliminate unnecessary pretrial detention to a reasonable rate.

“Too often in countries around the world, a person’s ability to obtain justice is

directly proportionate to their ability to afford it,” McCollum says. “Justice should

be available and accessible to everybody, and everybody should have their day in court.”

*Name has been changed for privacy