Alumnus George Cooper ('66) Reflects on Finding Love and Perspective in Pepperdine's Heidelberg International Program

George Cooper was running late.

A Dutch freighter ride across the Atlantic Ocean. A hurricane forcing ships ashore. A train from LeHarve to Paris. A turbulent taxi ride across the city of lights. Another train from Paris to Heidelberg, Germany. An afternoon of shaking hands and meeting a few new colleagues in Pepperdine’s first-ever year abroad program. This dayslong journey had worn out the Texas native.

At seven o’clock on the day of his arrival, Cooper was due to attend the welcome banquet at the Hotel Europaischer Hof. His internal clock, however, had different plans. Cooper was the last to arrive in the banquet room that night, and by the time he rolled in, only one seat was left unoccupied. Cooper slid into the lone dinner chair. He looked across the round table he had joined and found the blue-eyed stare of Sarah Webb.

A fan of movie musicals, scenes from Sigmund Romberg’s The Student Prince, in which a prince falls in love while attending school in Heidelberg, began to dance through Cooper’s mind. Was love at first sight real? Was he about to find out?

Rest and food took a back seat to love and hope. After being enraptured in lively conversation throughout dinner, Cooper and Webb agreed to go on a walk. After strolling through the German streets, they found a park bench where they could rest. There, Cooper worked up the nerve to ask Sarah a bold question, saying:

“I am Orpheus and would descend into Hades to rescue you. Will you marry me?”

In 1963 Pat Deese, a Lipscomb University government professor, introduced one of his history students to the concept of studying in Germany for a school year. He told his young charge about a school on the West Coast, George Pepperdine College, which was sending its first cohort of students to Heidelberg, Germany, to live and study immersed in a new culture. Cooper was intrigued.

“I was interested in how the Germans, who were some of the most educated and organized

of people, could give way to the Nazis,” he says, now 61 years removed from his Heidelberg

experience. “When we went, it was less than 20 years after the end of World War II.

There was still evidence of the impact of war.”

“I was interested in how the Germans, who were some of the most educated and organized

of people, could give way to the Nazis,” he says, now 61 years removed from his Heidelberg

experience. “When we went, it was less than 20 years after the end of World War II.

There was still evidence of the impact of war.”

This fascination with history led Cooper away from Texas and toward Europe. There he joined Howard A. White, a George Pepperdine College professor of history and later the president of the University, and his fellow students for a year of classes. However, the education that Cooper received ultimately had less to do with history books and more to do with perspective.

“One of the major things I learned was to see things from a different viewpoint,” he explains. “In other cultures and languages, the outlook and the experience are different from the American way of life.”

Cooper took advantage of his time in Europe. He traveled to Rome to witness Pope Paul VI offer a Christmas Mass in Latin, tasted the variety of Italian cuisines of Venice and Milan, toured the twisting streets of Innsbruck, Austria––site of the 1964 Winter Olympics––and attended all the cultural arts events he possibly could.

At a November 1963 piano recital hosted in Heidelberg, Cooper sat with other students wondering what to make of the rumors that something had happened to president John F. Kennedy back in the States. The worst of their fears was confirmed when the pianist returned for an encore to play Piano Sonata no. 2, otherwise known as Chopin’s funeral march.

Memory-making experiences were not challenging to cultivate in Cooper’s new and foreign world. They hid around every street corner; waited on each train ride; and sprang to life amid a community of new mentors, friends, and, ultimately, a fiance.

“Maybe” is how Sarah Webb responded to Cooper’s spontaneous proposal. “Maybe.”

It was enough for the love-stricken Texan to go on. In his mind, a wedding was in the future, which meant he’d have to purchase a ring for his bride to be. It also meant he’d need money, and a good portion of it, to turn this idea of a grand gesture into reality.

For six weeks after their stroll through the dark German streets, Cooper fasted, eating only soup for his meals. This was, he believed, the only way that he’d be able to save up enough cash to buy a wedding band for Sarah’s finger.

The romantic path toward engagement was not an easy one to navigate. Other suitors seemed bent on ruining Cooper’s fairytale love story. Maybe it was a soldier who sought to escort Sarah to church, or a fellow student who asked for her company at a local cafe. Either way, thought Cooper, the odds of him coming out on top and winning her hand were not strong.

Still, he tried his best. Class time was no longer a chance just to learn, but also an opportunity to impress Webb. Once the books were closed for the day, Cooper ran in the same social circle as his prospective wife. Within this group of friends, the two of them gallivanted through local eateries and coffee shops. Cooper did what he could in these brief moments of time to fan the flames of love in Webb’s heart. While he didn’t know everything about his potential bride to be, Cooper claims he knew “enough” to double down on his idea of engagement and see it through to the end.

Despite his best effort, there was a period of time, he admits, when he lost hope. Over the course of his six-week fast, Cooper began to realize engagement might not be the happy ending he was hoping for. But still, there was that word in the back of his head—the one that made the soup sufficiently filling: “Maybe . . . maybe.”

In October the phone in Cooper’s room rang. Sarah’s voice greeted him from the other end of the line. She asked him to meet her in the courtyard of the Hotel Golden Rose. Cooper agreed.

The scene was dark with dusk fast approaching. Cooper found Webb bathed in the dying day’s light and braced for whatever this conversation was about to bring—despair, joy, or more confusion. Webb cut straight to the point.

“I will marry you.”

Cooper’s time in Heidelberg not only offered him a chance to meet his partner in life—as though that were not enough—but it gave him a new perspective on the human condition as well.

At first, it incited his studies. He earned a master’s degree from Pepperdine College in 1966, leading him into academia. He served as a history professor at Harding College before stepping in to help his father with the family business in Texas. Now, as a veteran affairs chaplain, Cooper feels he has found his ultimate calling. In this role he works with retired service members struggling with post traumatic stress disorder, addiction issues, and other mental health challenges.

“Going to Heidelberg as a student allowed me to see things from the position of others,” says Cooper. “I don’t always understand their point of view or the decisions others make, but now I am able to engage with a broad range of people. I am curious about them and have the ability and wherewithal to ask questions, learn, and care.”

Although the course curricula in Cooper’s study abroad experience did not include lessons in intentionality or empathy, the Texas native naturally developed these attributes while navigating a culture different from his own. Sixty years later, the lessons he learned exploring the streets of Heidelberg, traveling Europe, and engaging with the customs of a new land blossomed in unexpected ways. Today Cooper is using his broadened perspective as a form of ministry, providing biblical wisdom to those in need.

“I’ve learned how to adapt and connect with things that are out of the ordinary for me,” he says. This openness to others’ views has not only enabled him to be a compassionate chaplain, but has also served him in finding new ways to relate––even after many years together–– as a life partner and spouse.

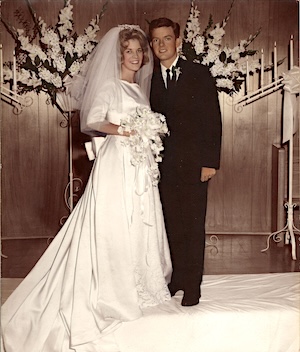

The wedding was moved up from August to June 20, 1964, a decision largely influenced by the couple’s extensive time on the phone. Upon returning home from Heidelberg—Longview, Texas, for Cooper and Anaheim, California, for Webb––the engaged couple kept in contact with long-distance phone calls that could stretch on for hours. These conversations proved so costly that the two families agreed something must be done, and in a hurry. The wedding bells rang out shortly afterward, and Sarah Webb became Sarah Cooper.

The couple began their married life in Los Angeles. Living near Pepperdine’s original

79th Street and Vermont Avenue campus, Cooper began taking classes in pursuit of a

master’s degree while Mrs. Cooper completed her course work and graduated from George

Pepperdine College. Yet, beyond earning these degrees, Sarah and George both reaped

rewards grander than a diploma. Their Pepperdine experience, domestically and abroad,

helped establish their family and their forward trajectory as followers of Christ.

The couple began their married life in Los Angeles. Living near Pepperdine’s original

79th Street and Vermont Avenue campus, Cooper began taking classes in pursuit of a

master’s degree while Mrs. Cooper completed her course work and graduated from George

Pepperdine College. Yet, beyond earning these degrees, Sarah and George both reaped

rewards grander than a diploma. Their Pepperdine experience, domestically and abroad,

helped establish their family and their forward trajectory as followers of Christ.

In 2018, after 54 years of marriage, George and Sarah Cooper traveled back to Heidelberg to visit the place where their paths first crossed and their love began to take root. As with all things, time had created change. Buildings were more modern, restaurants and vendors had closed down, and new, unfamiliar faces took the place of old friends.

George and Sarah were different as well. Five decades of navigating the obstacles of life together had catapulted them out of their 20s and well into their 70s—where a health condition began eroding one half of their love story. During this most recent trip across the Atlantic, Sarah was struggling with Alzheimer’s disease, leaving George to hold together the fragmented memories they still shared with one another at home and abroad.

However, when they arrived in Heidelberg, something happened. Despite all the cosmetic and colossal differences, the essence of the place was still the same. Strolling the German streets, like they had the night when Cooper proposed, George and Sarah were able to walk down memory lane together and appreciate the life they had lived as students and built together as adults. They were able to escape diagnoses, look back on that night in the courtyard—the one where Sarah Webb agreed to marry George Cooper—and remember the kiss they shared at the start of it all.

While memories and moments can be claimed by disease, love remains untouchable. The story of George and Sarah Cooper exemplifies this fact. To this day, against all the scientific odds, both husband and wife hold fast to their days in Germany and remember this as the place where their shared life began––where “I” became “we” in sickness and health.

“I don’t know what prompted her to say, ‘yes’ to me,” shares Cooper. “I don’t know. She just said, ‘I love you.’ That’s always been her classic response. I guess she wanted to keep me on my toes, and she has over the years.”