From Craigslist to Calling

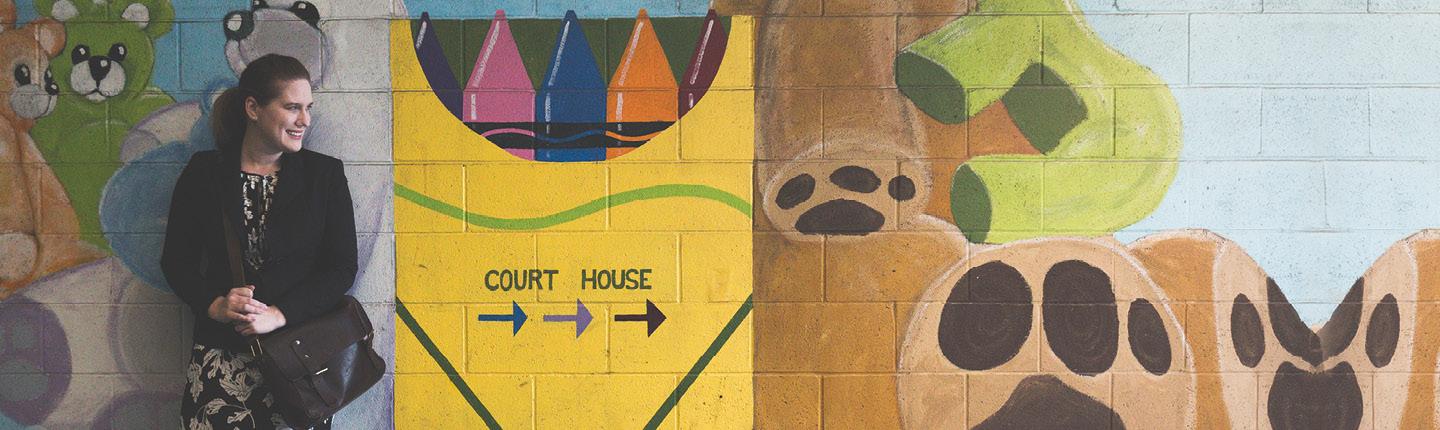

School of Law alumna Rebecca Harkness (JD ’07) pursues a life of purpose in children’s court

“I have to leave the room every time. I just can’t…”

Rebecca Harkness lets her voice trail off. There are simply no words for the pain in her heart as she watches a social worker remove a child from her mother’s arms. Knowing that the child’s well-being is at stake doesn’t diminish the profound sadness of the moment.

When Harkness began looking for work after graduating from Pepperdine Law, she thought that she might like to work with children. But the market for young lawyers was in decline, and she found herself scrolling through the job listings on Craigslist. It was there that she found a job representing parents in foster care cases, and a calling to serve families in need took shape.

Harkness later advocated for children in foster care cases and now represents foster care social workers for the L.A. County Department of Children and Family Services. Upon a judge’s approval, the department has the authority to remove children from their families, with the ultimate goal of protecting the safety of the county’s children. The number of cases and types of decisions that are made in children’s court are immense. In the face of overwhelming factors to consider, Harkness distills her focus to a single question: “How can I help the judge in this case make the best decisions for this child?”

Once jurisdiction over a child is established, the judge must resolve seemingly countless questions. Where is the child going to stay? When should the parents visit? May the parents see the child unmonitored? If a monitor is necessary, who will serve in that role? What services does the child need? What services do the parents need? Each decision must consider the child’s best interests and must be made in alignment with federal and state regulations.

Managing the latter can pull Harkness beyond the limits of lawyering. For example, government regulations require that a caregiver’s home have a certain number of bedrooms. Eager to retain custody of her grandchildren, the caregiver/grandmother in one of her cases found an apartment suitable under the law, but the rent was beyond her income. It fell to Harkness and the social worker to work out a budget with the caregiver so that she could then find a place she could afford.

“All I want to do is help people,” explains Harkness. “Even if it’s as small as ‘Let’s do a budget for you.’ I want that grandma to keep those kids because but for her, those kids will be in foster care with strangers. So if I can do little things to facilitate that, I will.”

Harkness appreciates working in California because placing children with relatives or friends is strongly supported by state law. Studies show, she says, that being removed from their parents and placed with strangers is very distressing for children. “It’s traumatic enough to be abused,” she explains. “When we can, we try to streamline these kids to someone they know, preferably a relative.” Harkness recalls one little boy she became very fond of. The child had tragically discovered the body of his mother after her suicide, and he was “just broken.” The boy had no relatives to look after him, but he did know the name of his mother’s best friend, who lived in Texas. It meant the world to him to get to know this friend, and Harkness and her colleagues found a way to make that happen.

California law is also supportive of expeditious family reunification, and recent changes in that area show an understanding of how difficult it can be for children to be in limbo. “Kids need to know what’s going to happen in their lives,” Harkness maintains. Now the parents of a child under 3 years old have six months to establish that they’re ready to reunify with the child, or the department will start looking at adoption.

But such systemic improvements can be double-edged. About five years ago, local papers published several critical articles condemning the department for a variety of failures. The results of the articles were positive—some of the attorneys are managing more reasonable caseloads, and the oversight of the department has substantially improved. They also spurred an even stronger effort to identify and secure every child in the county who is at risk, thereby protecting more kids and bringing more cases into the system. Harkness says she can see as many as 30 families in one day.

While the hallways of family court can be raucous and crowded, Harkness refuses to lose sight of the dignity of the people and the system she’s sworn to serve. “I try to make sure that I wear a suit every day, and I try to be as respectful as I can on the record, and to the parents and the children.” In the face of daunting, nonstop challenges, it might be tempting to just move on to the next case, Harkness says. “But for that parent, that child, that is their life—that’s a huge moment in their life. Something really big is happening for them.” So she steels herself and moves through her day, always checking herself with the critical question: “How can I help the judge in this case make the best decisions for this child?”