One Last Shot at Justice

For more than 25 years Gil Purcell (JD ‘83) has served as an advocate for victims of diseases caused by asbestos exposure.

It was December 2010. John “Jack” Casey waited with his wife Patricia in the courtroom as the trial began.

The case involved 12 defendants. Ten settled within weeks. The two remaining? FDCC, formerly Dinwiddie Construction, Inc., and Kaiser Gypsum Company, a manufacturer of joint compounds and wallboard materials.

A slew of experts were lined up. Among them were physicians, an oncologist, a pulmonologist, an economist, a cell biologist, a pathologist, an industrial hygienist, and an epidemiologist. They were all there to speak on Casey’s behalf.

A resident of San Francisco, California, Casey had worked as a plumber for more than 40 years before he retired in 2008. Most of his jobs were in the construction phases of the city’s high-rise buildings that supply some of the most picturesque views—the ones that residents and employees marveled at and even bragged about. But Casey wasn’t bragging. The fact was, he was dying.

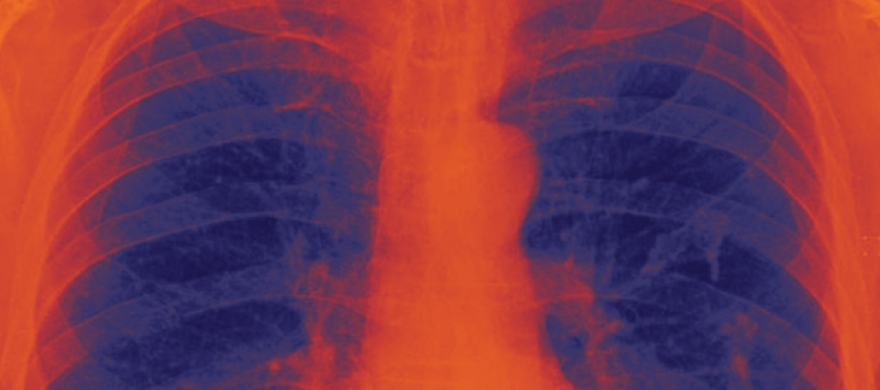

In 2009, just a year after retiring and weeks after developing symptoms, Casey was diagnosed with mesothelioma, an invariably fatal cancer of the lining of the chest cavity, caused from exposure to asbestos. He was given 12-18 months to live.

Gil Purcell

In researching similar cases to his own, Casey was led to Gil Purcell (JD ’83), a senior trial partner with Brayton Purcell LLP, who had more asbestos litigation experience under his belt than any other attorney in the country. Purcell walked into the courtroom that day armed with evidence that dated back nearly 100 years. There were articles from The Journal of the American Medical Associationfrom the turn of the 20th century— articles that didn’t mince words about the danger of asbestos. There was also a safety and prevention magazine that featured a November 1931 article of the same nature, all referencing medical research that proved that what was then referred to as “dust and fume disease” from exposure to asbestos was deadly. But the research had been ignored. Both companies claimed they knew nothing of the dangers until the 1980s.

They had gone through two juries by the time the case ended. In all, Casey was awarded more than $41 million, the highest verdict of its kind. He died in July 2011 at just 68, leaving behind his wife, two daughters, and three grandchildren.

“These cases are a matter of doing right by the citizens, by the tradesmen,” said Purcell, who will serve as the 2013 School of Law commencement speaker. “It’s horrific what these families have to go through. If I can make it so the client lives to see justice served, to know that their death isn’t in vain, then I have done my job.”

Purcell tried his first asbestos case in 1986, just three years out of law school, with Pepperdine Law alumnus Ray Boucher (JD ’84) and then trial judge Ronald George on the bench. George went on to become the chief justice of the California Supreme Court while Purcell built a private practice focused on cases involving victims of mesothelioma, as well as some against tobacco companies and malpractice lawsuits. He takes case after case of ordinary tradesmen that worked in naval shipyards, oil refineries, on tankers, and on construction sites.

“These families and their stories are from America’s ‘Greatest Generation,’” Purcell said. “You watch these men who were once very muscular and fit transform to nearly 75 or 80 pounds of almost nothing. They have no energy, no appetite, and are cachectic. They become sedentary. It is humiliating for them.”

For nearly every case there is a motion for preferential setting, meaning the judge is asked to prioritize based on the inevitable mortality rate. Like Casey, most of those diagnosed with mesothelioma only have a little more than a year to live. But it isn’t just the tradesmen that become victims.

“Part of what research from the 1950s has shown is that someone can be swimming in this dust and not even know it because the particles are so small,” Purcell said. “It’s disguised like any other construction dust.”

Asbestos

Because of that, a trail of asbestos dust often leaves the construction site with the workers and enters the home. Purcell has taken cases involving the wives and children of the workers—those who never stepped foot on a construction site, but because of tending to their husband’s or father’s laundry, they were exposed.

“This cancer is random in who it affects,” Purcell said. “I cannot tell you how hard it is to watch a man live through the guilt of something like this. There isn’t an effective form of chemotherapy or radiation yet that can treat it.”

Purcell’s cases extend throughout California and into his offices in Oregon and Utah. Regarded as one of California’s premier trial attorneys, Purcell was recognized in 2011 as Trial Lawyer of the Year, but he doesn’t perceive himself to be anything more than a vehicle for justice against what he refers to as “man-made disease and carnage.”

“Trial lawyering is a field that makes a difference,” Purcell said. “It is professionally rewarding to fight for these families. I learn from every trial, and I will keep at it as long as I can.”