Below the Line

As the Straus Institute for Dispute Resolution celebrates 30 years, Pepperdine Magazine reflects on the principles and players that have led to its indomitable track record

Los Angeles, 1986. A time when everybody wanted their day in court. Demand for judicial services was high and the courts were not equipped to promptly and efficiently adjudicate all the cases being filed. The time of filing to the time of trial in some jurisdictions was often five to six years and the cost of litigation was steadily increasing. Many lawyers simply could not afford taking on cases with small payouts, and attorneys were crying out for help.

There was mounting interest in resolving court cases through negotiation with the help of a mediator using a process called alternative dispute resolution (ADR), an emerging solution for the formal, time-consuming, and costly court litigation. As the justice system was slowly being reimagined, research was uncovering the great opportunity for the ADR field to change the way conflicts were resolved.

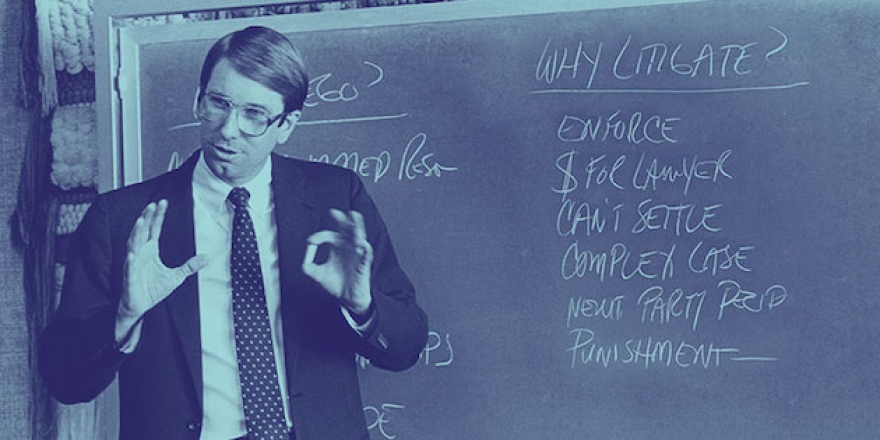

LaGard Smith, a professor at the School of Law, took notice of these developments and, along with Dean Ron Phillips and Assistant Dean Charles Nelson, caught the vision to develop a program at Pepperdine’s School of Law that addressed the shift in how society understands and reconciles conflict. Their goal was to meet the needs of the legal system by preparing Pepperdine students committed to resolving disputes more creatively and efficiently. Smith felt that mediation’s goal of reconciliation was consistent with the mission of the University and knew Pepperdine should be part of the great shift that was taking place in the legal world.

Nelson traveled to the Willamette University College of Law in Salem, Oregon, to visit a professor by the name of Randy Lowry (’74, MA ’77), a Pepperdine alumnus who was quickly becoming known as one of the nation’s leading experts in the field of dispute resolution. He hoped Lowry would be the perfect person to lead the charge at the School of Law.

Lowry joined the School of Law faculty in 1986 as the director of clinical law and, along with fellow faculty members, was tasked with creating an innovative experiential, skills-based ADR program. Two years later, the School of Law began offering its first academic program in dispute resolution, a 14-unit certificate designed to provide a supplementary experience for JD students. Lowry then hired Peter Robinson, a noted mediator and professional skills trainer, to serve as associate director of the dispute resolution program.

“Dispute resolution was becoming very important,” recalls Robinson, who, prior to Pepperdine, was the director of the Christian Conciliation Service of Los Angeles. “Our law school was preparing students for this reengineered justice system. Pepperdine was on the cutting edge of that shift.”

“A past presiding judge of the Los Angeles Superior Court confided that he believes a significant reason ADR was accepted by lawyers and judges in Southern California was the way Pepperdine approaches and teaches dispute resolution,” Robinson continues. “It’s done in a way that lawyers and judges can relate to and embrace. He said the practice of law changed and that we were part of that transition.”

The Straus Institute for Dispute Resolution was formally named in 1991 in honor of Leonard Straus—a Harvard-educated lawyer and CEO of Thrifty Drug stores— and his wife, Dorothy.

Together, Lowry and Robinson helped develop the framework for the program that continues to challenge students through tailored academic courses and programs, equips practitioners to address the emerging demands of their fields, counsels religious communities experiencing conflict around the world, and contributes to the research and development of new methodologies and practices in dispute resolution. The niche that the Straus visionaries carved out for the institute is distinctive for its commitment to bringing mediation and arbitration theory to life.

“The practice ADR is the thing,” confirms Robinson. “It is a big part of the Straus Institute. Everyone who teaches mediation or arbitration has served as mediators or arbitrators. We are committed to preparing practitioners.”

In 2005 Lowry and Robinson began discussions with Thomas Stipanowich, CEO of a Manhattan-based think tank, the International Institute for Conflict Prevention & Resolution, about co- sponsored skills training for corporate lawyers. When Lowry departed Pepperdine to take over as president of Lipscomb University, Stipanowich and Robinson began discussions that created a new leadership team for the Straus Institute in 2006. Stipanowich, a noted scholar whose work in arbitration and dispute resolution has been cited by the US Supreme Court and many other tribunals, joined the Pepperdine faculty as professor of law and academic director of the Straus Institute. As managing director, Robinson assumed responsibility for the day-to-day running of the institute.

Stipanowich drew upon his many contacts at large corporations and major law firms to create a new Council of Distinguished Advisors for the institute, including top lawyers from General Mills, Amgen, the US Air Force, and many other organizations. Meanwhile, Stipanowich’s scholarship and role in major national and international initiatives has greatly enhanced the institute’s academic reputation and its national and international visibility.

The institute currently offers both professional training and academic programs in dispute resolution, including a certificate program, a Master of Dispute Resolution, and a Master of Laws with concentrations in mediation, international commercial arbitration, and international commercial law and arbitration. The rigor and breadth of these programs attract students from all over the world, from those just entering their legal practice to senior judges and experienced attorneys.

When surveyed, many entering 1L students cite the dispute resolution program as their

number one driving force behind their decision to attend the School of Law. As Pepperdine’s

reputation grew, so too did its recognition. This year the Straus Institute was once

again ranked number one in dispute resolution by

U.S. News & World Report for the 12th time in 13 years.

“How has our comparatively little university been ranked higher than Harvard in this area of specialty? Part of it is the people,” says Robinson of the faculty and staff who have contributed to the Straus Institute’s global success. “Part of it is the vision, part of it is hard work, and part of it is grace. A lot of it is momentum.”

Robinson remembers a time when the Straus Institute was still building its reputation in the nascent world of ADR. “Now with the recognition,” he says, “the opportunities are very different. Now that we’ve established ourselves as a credible entity, we have to think about what’s next. How can we be a blessing and be used and bring glory to God and to Pepperdine?”

Today, people come from all over the world to study at the institute, often experiencing a transformation in the way they view and resolve conflict. Karinya Verghese (LLM ’15) experienced a dramatic change in the way she viewed her place in the legal world while working on large-scale real estate transactions at a corporate law firm in her native Australia.

“I was part of a system where people had less control of their disputes and how they were resolved,” she reveals. “I was deeply entrenched in the documents and slowly losing touch with the people behind the disputes.”

To counteract this disconnect, she began to shadow a mediator on her days off and spent her free time studying the art of mediation. After relocating to the United States Verghese decided there was more to her future in mediation than just passion. She moved to Los Angeles and explored LLM programs in dispute resolution and found herself at Pepperdine.

“The curriculum was exactly what I needed to connect with the things I felt were lacking in the market,” she recalls. “The experiential programs like the Mediation Clinic gave me a unique opportunity to flex my skills in real-life disputes and actually try different techniques to see what works and what doesn’t.”

Verghese now sits on the board of the Center for Conflict Resolution, the same organization that offers the Mediation Clinic to Straus students. As the associate regional director at FINRA’s Office of Dispute Resolution (West Region), her role is focused on arbitration, a practice she learned much about as a Straus Institute Research Fellow (2015-2016) working closely with Stipanowich after earning her LLM degree. At the time her passion was still in mediation, but one of her projects was helping Stipanowich make updates to the new edition of his arbitration textbook.

“It came full circle,” she says. “I never thought I’d work in arbitration, and now I’m working at an arbitration forum. That experience has been so incredibly helpful in forming my understanding of the rules of arbitration from an academic perspective as well as from Tom’s perspective as an arbitrator.”

At the Straus Institute faith is paramount and an integral part of the practice of law that has facilitated conflict resolution at local churches and enabled communication among divided communities around the world. In 2008 president Andrew K. Benton provided funding for Straus to start the PACIS Project in Faith Based Diplomacy, a unique international interfaith reconciliation program.

“The PACIS Project provides an academic ‘home’ for the education and mentoring of the next generation of faith-based diplomats and for new scholarship born out of field experiences,” said the late professor Tim Pownall in 2011.

That same year, Pownall, along with fellow PACIS director Brian Cox and codirector Michael Zacharia (LLM ’10) traveled to Egypt and Syria to lead members of different faith backgrounds towards reconciliation and put together workshops where individuals from both Muslim and Christian backgrounds could engage in dialogue and ask for and receive forgiveness. Later that year, the Association for Conflict Resolution, a nationwide association of mediators and arbitrators, recognized the PACIS Project and Pownall with their annual Peacemaker Award.

“Faith is not something that is way off to the side in most people’s lives. It’s a prominent driver in conflicts and has been for hundreds of years,” explains Lowry, who himself traveled as far as Nairobi, Kenya, where the PACIS team was summoned to aid in a conflict between American missionaries that had spread to churches in the community.

“Mediation isn’t about reviewing evidence and making a decision,” Lowry continues. “Mediation is about helping people make decisions for themselves that are durable long after we’ve left.”

In Porto Alegre, Brazil, Marcio Vasconcellos (LLM ’16) was working as a partner at a boutique commercial law firm that specialized in mergers and acquisitions and arbitration. Between translating international arbitration books in Portuguese, coaching law students participating in the Willem C. Vis International Commercial Arbitration Moot competition, and designing his own course in arbitration and contracts, Vasconcellos was handling three to five arbitration cases per year at Matter, Boettcher, and Zanini. After five years, he felt the need for structured, organized arbitration training and enrolled at Pepperdine.

Vasconcellos was drawn to the opportunity to learn from visiting professors, experts from around the world and across disciplines. He recalls the invaluable learning experiences he took away from classes with Maria Chedid, lead counsel in international arbitrations at Baker McKenzie, the second-largest international law firm in the world; Catherine Rogers, a leading scholar of international arbitration and professional ethics at Penn State Law and Queen Mary, University of London; and Linda Silverman, codirector of the Center for Transnational Litigation, Arbitration, and Commercial Law at NYU.

Hailing from a country where civil law is the method of justice, he also credits his experience at Pepperdine and his subsequent career in Los Angeles for giving him an international perspective of law traditions.

“At the end of the day, arguments are arguments, and everyone is taking different avenues to reach the same goals,” he says. “Pepperdine was able to help us translate the differences and similarities between civil law and common law and to help us see that it doesn’t matter which tradition you come from. Everything is different, yet everything is the same. That was helpful to me as I made my foray into the US practice.”

“Go below the line!” Those four words traveled across a restaurant dining room in Malibu where Lowry was having lunch during a visit to Pepperdine a few years ago. He knew that the words were meant for him, and he knew exactly what they meant. The person who shouted the phrase was a former student of Lowry’s who, over 10 years later, still credited her law school professor with changing the way she approached negotiations in her professional life. She explained to him that the phrase contributed to her professional success.

When explaining negotiation, Lowry draws a line at the top of a page. Above the line are the facts and evidence collected from both sides of parties. Below the line are the interests and needs of the individuals involved. The items below the line, Lowry insists, are key to understanding the driving forces behind conflicts and are often most powerful in helping resolve them.

“Most conflicts begin as a people problem. Lawyers make them a legal problem,” Lowry says. “We mediators go back and try to figure out the people problem again, and when we figure that out often we’re able to be helpful in coming to a resolution.”

Stipanowich, who as a young construction litigator was asked by a client, “Isn’t there a better way to resolve our disputes?” now sees the “go below the line” approach as underpinning fundamental changes in the way 21st-century lawyers practice law.

“Traditional legal education focused on substantive legal concepts is necessary, but not sufficient,” he explains. “We must embrace a holistic approach to the practice of law that sees our clients as whole people that bring particular hopes, fears, values, and needs to the table. Our program is about giving lawyers the tools to serve the whole person.”