One Long Day

Five years after surviving a terrorist attack, alumna La’Nita Johnson (’14) continues to make sense of the unthinkable

As an international studies and Hispanic studies major at Seaver College, La’Nita Johnson fell in love with service. Volunteering with the school’s programs, most notably as the coordinator of the volunteers who taught English to day laborers as they waited for daily work, was the cornerstone of her Pepperdine years. “I saw what language and labor inequity looked like in our community. It was my first experience witnessing this type of hardship and development challenges,” she says. “I lived it every week.”

When she began working after graduation at GE Capital, the financial services division of General Electric, her passion for service led her to arrange a mission trip through her employer’s partnership with the nonprofit buildOn to construct schools in developing countries. Traveling to Burkina Faso, a small landlocked country in West Africa in January 2016, Johnson planned to spend seven days serving with the organization, after which she’d do some sightseeing. Her week in a rural village—which included starting the construction of a school for both boys and girls, getting to know the villagers (through translators of Moore and English), and partaking in traditional activities such as making shea butter—was a deeply gratifying experience.

Returning to the city at the end of their trip, Johnson and her coworkers planned a dinner out in a Western-style cafe to celebrate their achievements and their time together. Waiting inside for the entire group to arrive, she took advantage of the Wi-Fi to call her parents, send them some photos of her time in the village, and tell them she was safe. Approximately 15 minutes after the whole team was assembled and seated together in the back of the cafe, the scene would take on a markedly different appearance.

A Morpougha village elder gifts Johnson a traditional Burkina cloth during a farewell

ceremony.

Suddenly several people entered the restaurant and started firing indiscriminately. In the melee, Johnson was able to flee to the restaurant’s bathroom with several other patrons, including some from her group, where they remained in hiding for about two hours while the shooters, who were later identified as Al-Qaeda militants, threw bombs into the cafe, left, returned, started shooting again, and continued bombing the building.

“What I will always remember,” she says, “is the sound of phones going off. There was a lot of screaming and crying and glass shattering. I heard a child screaming. It was the owner’s son. I later found out he was killed.”

Johnson eventually escaped from the restaurant, but with the perpetrators of the violent act still at large, the streets remained unsafe. She hid in an alley with another woman as the shooting continued all night. She cut her toe quite badly and recalls that as the hours went by she had thoughts that were both quite logical (“My toe will have to be amputated”) and seemingly ridiculous (“I’ll never wear sandals again”).

About 16 hours after the attack began, Johnson was found by the police and was taken to a hospital for treatment. Members of her party located her there and told her that two people in her group had been killed in the attack. Later that day she was evacuated from the country along with her companions.

Everything Was Different

Johnson returned to work in Chicago but found that her former easygoing state was no longer accessible to her; she couldn’t remember how she’d moved fearlessly through the world. Her job began to feel toxic to her, and she was forced to go on disability leave. She felt the need to understand what happened, to herself and in Burkina Faso, and she started researching the event online. This led to two discoveries.

The first was about the dearth of information for civilians with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). It took little time to learn that the mental health issues she was experiencing fell outside the traditional conversations of healing from trauma. “When you search ‘what to do after a terrorist attack,’ most of the information addresses veterans that have suffered IED bombings or returned from war,” she says. “At the time, I was a 22-year-old middle-class African American girl, and my experience was nothing like that. I wanted to know, for example, why I was so tired when I hadn’t really done anything that day.”

Eventually, Johnson decided to fill the void. She created a website, ptsdoutloud.com, as both a place to share her thoughts and as a resource and safe space for those who have undergone trauma. “Instead of holding it in or isolating myself, which is what I’d been doing, I thought, ‘Just write about it.’ There were a lot of attacks after mine, and I thought perhaps others might stumble on what I’d posted and relate.”

Johnson sees herself as a devoted advocate for a public that is more accepting and knowledgeable about mental health. “For a while after the attack, I wished I’d been shot, just so people could understand the ongoing nature of the trauma. They weren’t satisfied that the mental anguish of having lost two members of my group and experiencing such evil and death was a sufficient cause of my distress.” She would also like to see a wider understanding of the extent to which PTSD is experienced. While it may arise after a traumatic event like a car accident or a natural disaster, it’s also a largely unidentified experience in communities of color. “It doesn’t look like the veteran experience,” says Johnson. “But in communities where people are impoverished and denied access to employment, there will be individuals experiencing high levels of PTSD,” she says. “But when it doesn’t look like how we see it in the news, as a nation we don’t say ‘that’s a problem.’”

Many people, including some who were victims of the same terrorist attack, have made connections with Johnson through her site and blog. She’s heartened when she learns that she’s touched them when they respond to her posts with messages like, “Thank God, I’m not crazy.” She’s developed a very individualized approach to speaking with others about healing from trauma and moving with a traumatic event into their future.

“When I was able to stop considering what other people wanted for me and stop looking externally for validation about what the experience meant is when I was able to make a lot of changes and have harder conversations,” she says. Now she asks others, “What does it mean for you? How do you want to make sense of what occurred for you?”

Making the Difference Matter

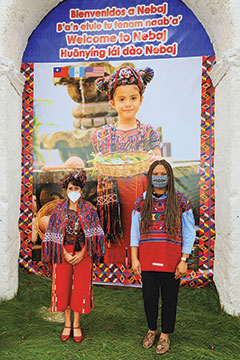

Johnson meets with a Nebaj Indigenous representative during USAID’s launch for the

Alliance for Education.

For Johnson, making sense of what occurred was essentially her second discovery. While reading reports of the attack, she learned that the gunmen who conducted it were youths. A co-survivor told her that while hiding under a car that day, he noticed that they were not even wearing shoes. “I was heartbroken,” she says, “that this was an option for kids. I’d been instilled at Pepperdine with the need to know why God put me on this planet and to ask how I was going to serve in the world. I then asked myself, ‘How do I make sure kids don’t choose this as an option?’”

Johnson determined that she must be an educator, but having spent all her savings on counseling, she was not in a position to go back to school. She applied for some foreign service fellowships and was awarded a Payne Fellowship, which paid for her graduate studies, offered her two internships, and, thereafter, helped start her career in the foreign service. She is now an education officer in Guatemala with USAID working on youth workforce development programming with local youth training nonprofits. Her efforts help ensure that the country’s youth don’t face an empty future and that they have opportunities to continue their education, be trained to start a business, or obtain employment.

In addition to directly assisting the youth of Guatemala, Johnson is also committed to broadening the diversity of the foreign service. “One of the most gratifying aspects of my job is mentoring new Payne Fellows and prospective applicants,” says Johnson. “It is a fellowship to enhance traditionally underrepresented groups, and if I can bring more people of color into the foreign service to converse with the people we’re impacting, I’m grateful for that experience. My biggest dream,” she continues, “is to create an organization, maybe an afterschool program, that works with Black and brown youth for professional development. People of color are underrepresented in these types of leadership roles.”

Although Johnson’s life was irrevocably changed by her service trip to Burkina Faso, her devotion to helping others has only been strengthened. “In the Pepperdine Volunteer Center, we had deep pedagogical conversations about what inequity looks like, and those conversations stayed with me.” She is also clear that the University’s continued dedication to involvement in service programs will be invaluable to both students and the larger community. “We have to find ways to not only have the conversations at an academic level,” she says. “We have to also get our people out there serving.”